How can you motivate students without motivation?

Sadly, it is not uncommon for students to feel like they hate school. Although this is a complicated issue with many points of analysis, student motivation is an incredibly important aspect of it. Most likely, when you were a student you struggled with being motivated at school. If you are an educator, you will most likely have encountered a situation in which you felt like you weren’t engaging students in your class. You may have even said that your students don’t seem to have motivation in the classroom, and felt helpless faced with such a challenge.

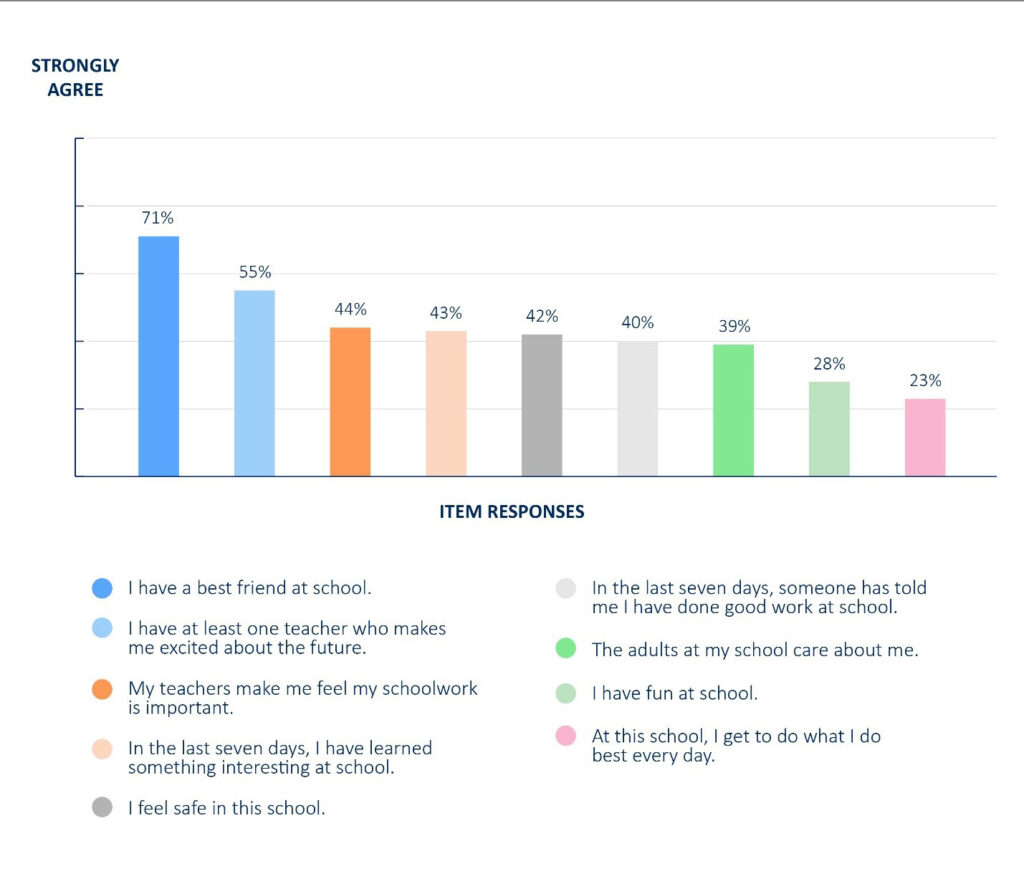

Motivating and engaging students is a far too prevalent issue with far reaching consequences for them and their learning process. This situation could be explained by the fact that educators’ beliefs about what motivates students to learn is different from what actually motivates their students. Research from Gallup delved into trends about what is working in our classrooms and what else we need to be doing to maximize student engagement.1 Results showed that while things like feeling valued and safe, having friends and feeling that what they learn matters is important for motivation and engagement, most of them report not experiencing some of these at their schools.

In the following lines we will discuss some engagement strategies for students and some ways in which you can increase student engagement and motivation.

Expectations

Educators often set expectations about their students’ abilities based on their past academic performance. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with that, the beliefs they develop affect how they deliver instructions, create group practices, and influence how they evaluate them. Research reveals that educators tend to provide a more supportive emotional climate, clearer feedback, more attention, more instructional time, and more learning opportunities overall for their high-expectancy students relative to their low-expectancy students. Such differential treatment can magnify the actual differences in achievement between high- and low-performing students, rather than help the lower performing students perform better.

So, how do we prevent this? It would be impossible for educators to not have expectations about their students, so the solution is teaching educators how to manage those expectations.

Challenge and meaning

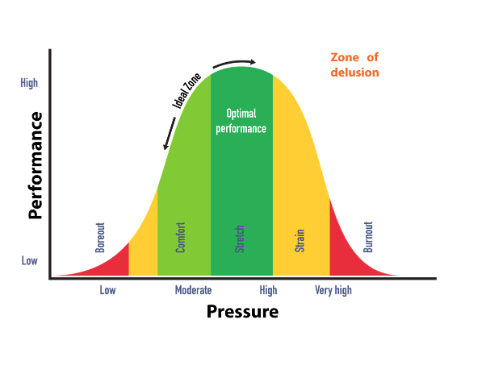

Engagement and motivation in the classroom isn’t just about being in class, it is also about what students do while they are there. When it comes to evaluating how motivating or engaging a task can be, it is important to consider how challenging it is. If a student thinks they can’t succeed at a task, they’re not going to be motivated to try it. So, students have to feel efficacious as learners, and they have to see that there’s going to be a path for them to succeed at the task. If material is too foreign or challenging, students can easily disengage; however, this is also true when material is too easy. A great way to understand this is by looking at the Yerkes-Dodson Curve.

This image shows us that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal (stress), but only up to a point. When the level of stress becomes too high, performance decreases. Overall, finding the right level of challenge sets students up for success, as they will believe they can succeed and thus perceive that it is worth the effort to engage with the material.

Active learning

At some point in your life as a student, you were likely expected to learn by sitting quietly and listening while an educator lectured. This approach tends to overload our working memory, which often leads to disengagement.

Learning and engagement decrease when educators lecture and when they expect students to practice independently; both lead to passive compliance. John Hattie’s research reveals that on average, educators talk between 70% and 80% of the time they are teaching, while only a small fraction of that talk time (usually 5% to 10%) promotes engagement amongst their students. Unfortunately, research reveals that most classrooms worldwide still employ this teaching approach, despite the fact that it is not conducive to learning and has been proven ineffective. Classroom environments that promote engagement have students listening to educator-talk less of the time and actively problem-solving collectively more of the time. This type of learning has been demonstrated to increase engagement between students and their learning, which is positively correlated to academic achievement.

If at any point you find yourself doubting one of the points we have discussed here, it can be useful to ask yourself the following questions: Will the students’ effort lead to higher performance? Will higher performance lead to rewards? How desirable are the rewards? Motivation plays a critical role in guiding the direction, intensity, persistence, and quality of the learning behaviors in which students engage. When learners find positive value in a learning goal or activity, expect to successfully achieve a desired learning outcome, and perceive support from their environment, they are likely to be strongly motivated to learn.

References

- Gallup Student Poll. (2015). Engaged today — ready for tomorrow. http://www.gallupstudentpoll.com/

- American Psychological Association (2015). Top 20 principles from psychology for preK–12 teaching and learning. http://www.apa.org/ed/schools/cpse/top-twenty-principles.pdf

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Taylor & Francis.

- Wieman, C. E. (2014). Large-scale comparison of science teaching methods sends clear message. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8320. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.140730411

- Burkholder, E., Blackmon, L., & Wieman, C. (2020) What factors impact student performance in introductory physics? PLoS ONE 15(12): e0244146. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0244146

- Burkholder, E., Salehi, S., Sackeyfio, S., Mohamed-Hinds, N., & Wieman, C. (2021). An equitable and effective approach to introductory mechanics. Cornell University: Physics Education. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2111.12504

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Science of Learning Insights to Your Inbox.

Subscribe to receive these evidence-based insights. Together let’s deepen our understanding of the science behind effective teaching and learning.